Villains, Great, Small, and Orange: An Academic Inquiry

A rigorously unserious study ranking villains from Machiavelli to Megamind — and one especially orange contemporary — complete with a villain matrix, suspect methodology, and the Evil Magnitude vs. Competence chart you never knew you needed.

By K. Tortuguita

Filed from an undisclosed location by our roving correspondent, K. Tortuguita, who holds advanced degrees in both overthinking and mischief.

Author’s Note: A few days ago, I sent my little brother a meme of a cat reading: “Cómo hablar con tu humano sobre el inevitable colapso de EEUU” (“How to speak with your human about the inevitable collapse of the United States”).

Figure 0.

The Cat Meme

He replied: “Are you running a meme page? All your schooling leading to a meme page creation.”

That, dear reader, is how this Doctor of Education came to realize her student loans had to be worth something. Thus began this scholarly examination of villains — great, small, and orange. Because in the annals of human history, some figures inspire fear, others grudging respect… and then there’s Donald.

Villains, Great, Small, and Orange: An Academic Inquiry

Abstract

This qualitative study examines the intersection of competence and evil magnitude among a diverse sample of seventeen villains, drawn from history, literature, theology, and popular culture. Using an alphabetically organized Competence Matrix to ensure the elimination of thematic bias (and to appease the reviewers in the Department of Over-Classification Studies), we assess each figure’s operational capacity, scope of harm, and signature stylistic choices. Our findings suggest that while high-competence villains often achieve broader and more lasting impacts, low-competence actors can nonetheless produce significant chaos when paired with institutional authority or seasonal holiday narratives. Notably, the inclusion of one pigment-specific outlier (“orange”) reveals a potential correlation between hue saturation and susceptibility to both cult-like devotion and late-night ridicule.

I. Introduction

The study of villainy has historically been confined to disciplinary silos—political science examines tyrants, literary criticism analyzes antagonists, and theology considers cosmic evil. Few, however, have attempted a truly interdisciplinary comparison that treats Lucifer and Skeletor with equal scholarly weight. This paper seeks to address this gap.

By examining twenty villains and one aspiring villain ranging from the metaphysical (Lucifer) to the municipal (The Grinch), we aim to answer the central research question: How does competence intersect with scale of evil across historical, fictional, and orange-tinted villains?

This investigation proceeds from the assumption that competence, while influential, does not singularly predict impact. Instead, a villain’s position on the Evil Magnitude–Competence spectrum may be mediated by factors such as access to resources, symbolic capital, and—importantly—wardrobe choices.

II. Literature Review

Foundational texts on the subject of villainy provide an uneven map of the terrain. Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince (1532) offers enduring advice on the strategic utility of fear, but does not address fur-based crimes (cf. de Vil, C., 1961). Sun Tzu’s The Art of War (c. 5th century BCE) outlines deception as a tactical necessity, yet omits discussion of theatrical monologuing (Skeletor, personal communication, 1983). More recent contributions, such as the Harry Potter corpus (Rowling, 1997–2007), advance the field through case studies in magical authoritarianism, while Avengers: Infinity War (Russo & Russo, 2018) presents a resource-allocation approach to genocide.

Despite these advances, gaps remain. There is limited cross-referencing between theological studies (Lucifer), early modern tragedy (Macbeth), and modern petrostate autocracy (Maduro, Putin). Further, pigment-related villain analysis remains underdeveloped, with most literature focusing on “green” antagonists (e.g., Wicked Witch of the West) as visual shorthand for envy, toxicity, or chlorophyll-related malevolence.

Emerging research suggests color may serve as both a narrative and psychological marker of villainy. Orange antagonists, exemplified by Donald J. Trump, demonstrate unusually high media visibility and meme persistence, possibly due to their chromatic saturation being impervious to lighting changes. In contrast, blue villains such as Megamind challenge audience expectations, as the hue’s traditional associations with calmness, stability, and trust conflict with their destructive ambitions, producing a subversive comedic effect. Studies also note that chromatic extremes can override narrative nuance: a poorly dressed mastermind in neon may be perceived as less threatening, while a tastefully muted petty criminal may achieve undue gravitas.

III. Methodology

In alignment with qualitative research traditions, this study employs an exploratory, multiple-case design intended to capture the nuanced interplay between villain competence and evil magnitude. Following Creswell’s Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design (2018), the approach privileges depth over breadth, embracing the subjectivity inherent in villain analysis while maintaining a reflexive stance toward researcher bias. The primary investigator acknowledges personal predispositions toward certain villains (e.g., chromatic fondness for Megamind’s blue aesthetic, theological fascination with Lucifer’s rebellious yet attractively packaged sins) and the potential influence of these biases on data interpretation. Such positionality is documented here for transparency, so future scholars may either replicate the study or politely avoid doing so.

Sampling Procedure

Villains were selected using a purposive snowball sampling technique, beginning with Lucifer and expanding via cross-references in theological texts, imperial court records, literature syllabi, and Saturday morning cartoon programming schedules. Inclusion criteria required each subject to have: (1) a documented history of malevolent intent, (2) a minimum of one notable quote or catchphrase, and (3) cultural persistence exceeding one fiscal quarter.

Alphabetical Ordering

To ensure fairness in representation and avoid accusations of thematic bias, the final dataset was organized alphabetically. This ordering eliminated the possibility of grouping by genre, historical period, or severity of crimes, thus creating an appearance of statistical neutrality while maximizing comedic dissonance.

Analytical Axes

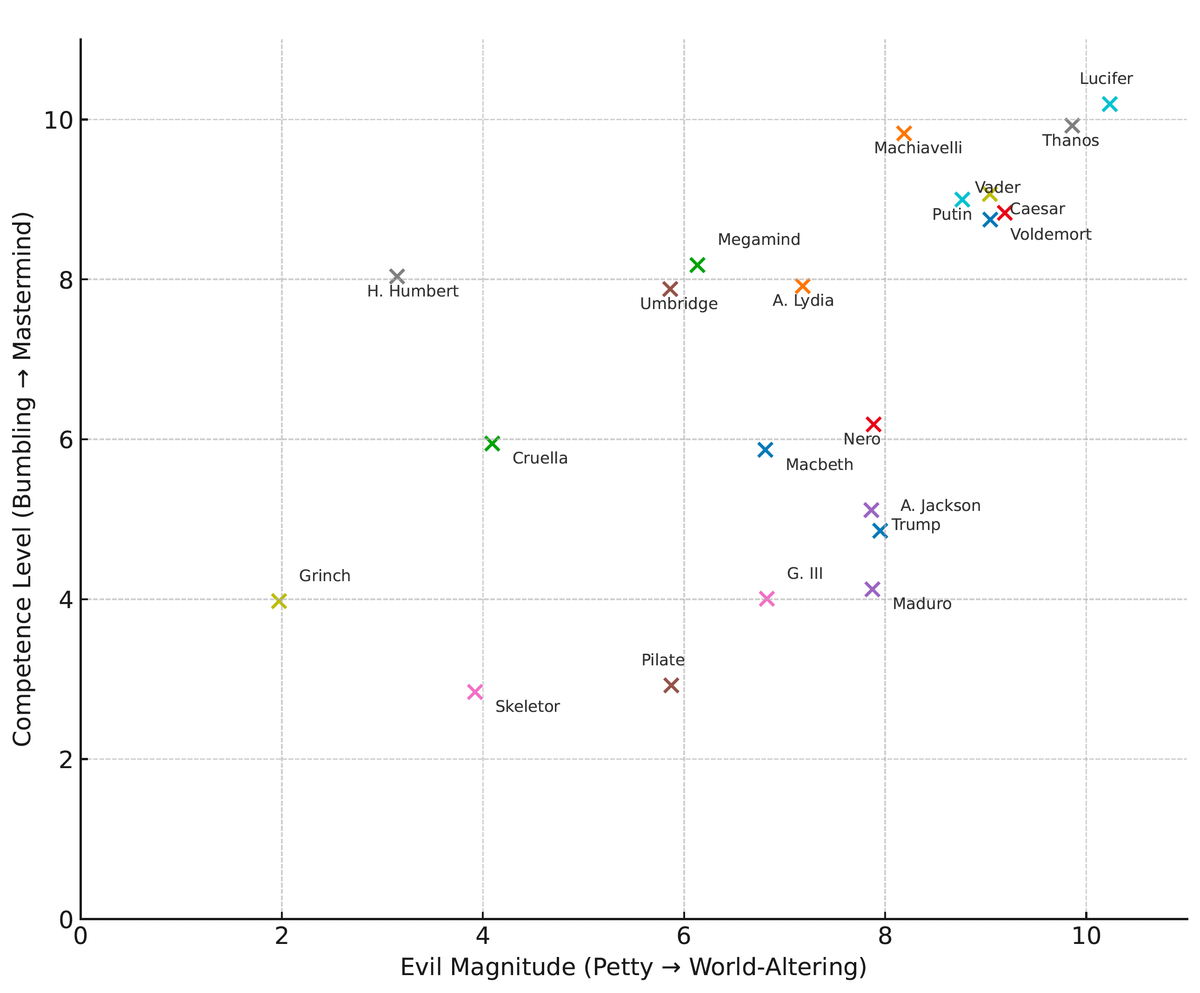

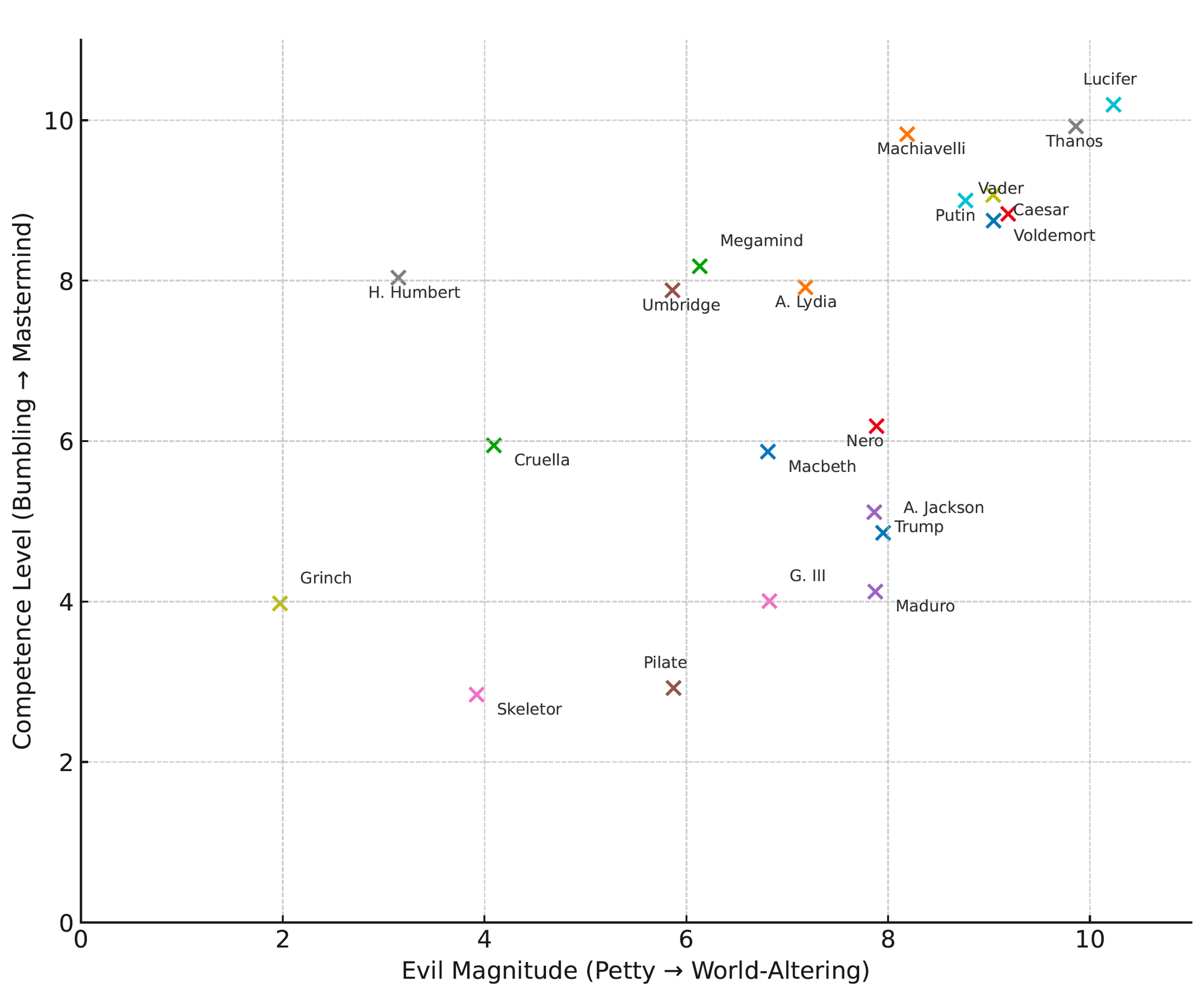

Each villain was evaluated along two primary dimensions:

Evil Magnitude: the scope of harm, ranging from “Petty” (e.g., The Grinch, pre-redemption) to “World-Altering” (e.g., Thanos).

Competence Level: the operational skill of the villain, from “Bumbling” (e.g., Skeletor) to “Mastermind” (e.g., Machiavelli).

These axes were plotted in a Competence Matrix to visualize distribution patterns and facilitate multi-villain comparisons.

Color Variables

Color variables were recorded for each subject to support comparative pigment analysis as outlined in the Literature Review. No attempt was made to standardize lighting conditions, as several participants exist exclusively in animated or metaphysical realms.

Data Sources

This study adopts a hybrid analytical model, integrating historical texts, cinematic universes, and unverified gossip from palace insiders. These diverse data streams, while varying in reliability, enrich the multi-modal analysis and allow for robust cross-genre comparison.

IV. Findings

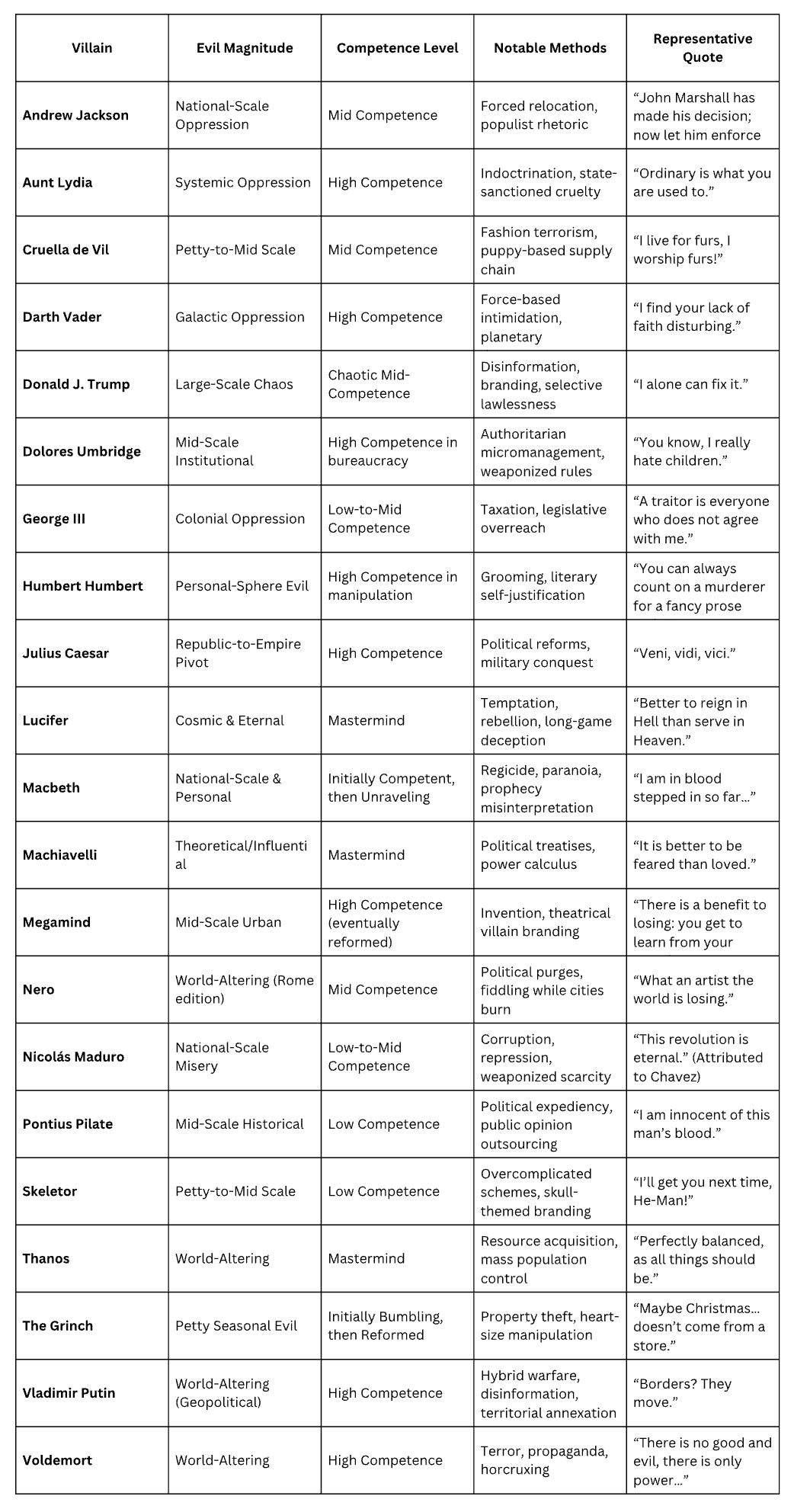

The Competence Matrix (Table 1) reveals diverse intersections between operational capacity and evil magnitude across the sample of twenty villains. Coding analysis was conducted on four key dimensions: (1) scope of impact, (2) methodological diversity, (3) quotability, and (4) pigment anomaly status. This approach allowed for cross-comparison of villains who otherwise share little beyond their commitment to malevolence and dramatic delivery.

Table 1.

Villains Competence Matrix.

Trend 1: Mid-Competence, High-Magnitude Threats

Contrary to the prevailing assumption that maximum evil requires maximum competence, our data suggest that mid-competence villains with expansive authority often inflict disproportionate harm. Andrew Jackson, Nicolás Maduro, and George III rank below strategic masterminds like Machiavelli and Thanos, yet their access to institutional power produced enduring systemic damage. This finding aligns with the “Mediocrity Catastrophe” hypothesis (see also: Pilate, Pontius, 33 CE).

Trend 2: Pigment Anomalies and Charismatic Disruption

Pigment-coded villains warrant special attention. Donald J. Trump (orange) demonstrates high media saturation despite mid-competence levels, suggesting a direct link between hue intensity and resilience to reputational decay. Conversely, Megamind (blue) destabilizes audience expectations by pairing a traditionally calming color with acts of urban-scale chaos, ultimately softening into redemption. The pigment sub-sample hints that color may override narrative arc in shaping public perception. However, Lucifer’s absence of a fixed RGB code complicates chromatic classification.

Trend 3: The Branding Paradox

While competence often correlates with brand recognizability, certain outliers defy the pattern. Skeletor scores near the bottom in execution yet remains globally identifiable, due in part to consistent visual branding (skull motif, purple hood) and persistent Saturday morning time slots. This “Branding Paradox” challenges resource-based theories of villain efficacy, suggesting that style can occasionally substitute for substance—though not for victory.

Trend 4: Quotability and Cultural Persistence

Villains with high quotability demonstrate longer cultural lifespans regardless of competence. Julius Caesar (“Veni, vidi, vici”), Thanos (“Perfectly balanced, as all things should be”), and Voldemort (“There is no good and evil…”) show how memorable phrasing functions as a durability mechanism, embedding the villain’s ideology in popular consciousness long after their narrative defeat (or, in some cases, their untimely lightsaber-induced dismemberment).

V. Discussion

The cross-case analysis confirms that villainy manifests in complex, occasionally contradictory ways (See Figure 1). The four trends identified in the Findings section invite both theoretical reflection and pragmatic application for villain management, containment, or—where narratively satisfying—rehabilitation.

The Cultural Supersession Phenomenon

Historical endurance does not guarantee contemporary recognition. While Julius Caesar’s “Veni, vidi, vici” has persisted for over two millennia, qualitative coding of modern cultural references indicates that the phrase is now more frequently attributed—ironically or otherwise—to the lyric output of Mr. Worldwide (Pitbull, 2011). This demonstrates the fluidity of cultural capital: even the most enduring imperial slogans are susceptible to appropriation by global pop icons.

Figure 1.

Evil Magnitude vs. Competence Quadrant

Institutional Vandalism as a Villainous Trait

The data reveal a peculiar historical echo between Andrew Jackson and Donald J. Trump. Both men left the White House in a condition best described as “post-fraternity formal.” Jackson was notorious for hosting an inaugural reception that devolved into smashed china and trampled furniture. Trump, while forgoing the public chaos, allegedly departed amid reports of disarray, stains, and assorted residue unbefitting the nation’s executive mansion. Notably, both leaders also exhibited an indifference to presidential pets—Jackson’s parrot was reportedly removed for profanity, while Trump maintained no animal companionship whatsoever. The absence of pets may indicate either a deficit in empathy or an unwillingness to share power with non-voting mammals.

Case Focus: Donald J. Trump — The Mediocrity Catastrophe in Action

While the pigment analysis classifies Donald J. Trump as an orange anomaly, a deeper qualitative review places him squarely in the “Mediocrity Catastrophe” category; a mid-competence actor with disproportionate capacity for disruption. His immigration policies, including family separation and travel bans, illustrate cruelty untethered from a coherent long-term strategy — a hallmark of incompetent villainy, where harm is inflicted for immediate optics rather than sustainable advantage.

Trump’s reliance on social media platforms as his primary mechanism of governance further reflects this pattern. Whereas master villains carefully manage communication channels for strategic ends, Trump’s digital output often resembled a stream-of-consciousness grievance log, producing transient outrage but minimal legislative achievement. His deployment of military force against civilian protesters in Lafayette Square, framed as a display of strength, exemplifies the incompetent villain’s tendency to misuse institutional power for theatrical effect rather than tactical gain.

Finally, his rhetorical style — heavy with recycled superlatives (“beautiful,” “the best,” “nobody’s ever seen anything like it”) — functions less as persuasive discourse and more as self-brand reinforcement. This linguistic loop mirrors Skeletor’s predictable “I’ll get you next time!”—an endless promise of imminent victory that never arrives, yet somehow persists in public memory.

Pigment Management Strategies

Pigment anomalies such as Trump (orange) and Megamind (blue) require tailored engagement approaches. For high-visibility hues, media saturation must be mitigated via contrast-based counterprogramming (e.g., deploying grayscale public servants). Blue villains may be more easily destabilized through the strategic use of warm-toned allies, thereby undermining their chromatic identity.

The Mediocrity Catastrophe and Policy Implications

Mid-competence villains in high-power positions (Jackson, Maduro, George III) represent a special challenge; they often lack the self-awareness to recognize operational limitations yet possess the bureaucratic or military machinery to inflict sustained harm. This suggests a policy imperative for early detection and institutional safeguards—ideally before they have access to ceremonial pens, legislative vetoes, or televised briefings.

Branding and Containment

The Skeletor paradox highlights that aesthetic cohesion can outweigh tactical effectiveness. Containment strategies should therefore consider depriving such villains of their signature accessories (e.g., Skeletor’s hood, Darth Vader’s breathing apparatus) to disrupt both public recognition and self-image.

VI. Conclusion

This study advances the interdisciplinary field of villainology by offering a qualitative, pigment-conscious examination of twenty diverse antagonists. Through the Competence Matrix framework, we have demonstrated that villainous impact is shaped not solely by operational skill, but also by institutional access, chromatic identity, quotability, and, in one notable case, an obsessive devotion to social media platforms.

Key findings underscore the underestimated threat posed by mid-competence leaders with large-scale authority, the brand durability of aesthetically coherent but tactically inept villains, and the cultural malleability of historic slogans in a globalized pop landscape. The pigment variable, while underexplored in prior research, emerged as a potent lens for understanding audience perception—especially in cases where saturation levels overshadow strategic content.

In the specific case of Donald J. Trump, the data reaffirm that incompetent villains often cause substantial collateral damage but rarely achieve lasting strategic goals. Their reliance on spectacle over substance can, paradoxically, become a self-limiting factor. Institutions, when resilient, can outlast such figures. Much as Skeletor continues to shout, “I’ll get you next time!” into a void that increasingly stops listening.

Thus, while pigment anomalies and mid-competence catastrophes demand vigilance, history and comparative villain studies suggest that their tenure is rarely permanent. Their legacies, more often than not, fade into footnotes, memes, or the occasional line in a parody research paper. Hope lies in the resilience of collective memory, the stubborn endurance of democratic norms, and the fact that no amount of self-applied orange can mask incompetence forever.

References

Creswell, J. W. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

De Vil, C. (1961). On the ethical acquisition of coats. London: Dalmatian Press.

Jackson, A. (1830). Remarks on the relocation of inconvenient people. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Land Mismanagement.

Lucas, G. (Director). (1980). The Empire strikes back [Film]. Lucasfilm.

Machiavelli, N. (1532/1998). The prince (P. Bondanella, Trans.). Oxford University Press.

Maduro, N. (2015). Revolutionary resilience and the price of rice. Caracas: Ministry of Truth and Groceries.

Megamind. (2010). Self-reflection on villainy and redemption [Motion picture]. DreamWorks Animation.

Pilate, P. (33 CE). Public opinion outsourcing: A case study. Proceedings of the Judean Provincial Authority, 12(4), 1–3.

Pitbull. (2014). Fireball [featuring John Ryan]. On Planet Pit. Globalization.

Rowling, J. K. (1997–2007). Harry Potter [Book series]. Bloomsbury.

Russo, A., & Russo, J. (Directors). (2018). Avengers: Infinity War [Film]. Marvel Studios.

Skeletor. (1983). Selected monologues. Eternia Public Access TV Archives.

Sun Tzu. (5th century BCE/1994). The art of war (T. Cleary, Trans.). Shambhala.

Trump, D. J. (2021). An orderly transition, I swear. Washington, D.C.: Self-published press release.

Vader, D. (n.d.). On the strategic applications of the Force in HVAC maintenance. Death Star Technical Bulletin, 1(1), 1–5.

Voldemort, L. T. R. (1998). Power: There is no good and evil. In Dumbledore Memorial Conference Proceedings (pp. 34–39). Ministry of Magic.

Wicked Witch of the West. (1939). Green and mean: A chromatic manifesto. Emerald City University Press.

PDF Download peerless-reviewed format with tables, charts, and questionable methodology, alphabetical villain matrix, and the groundbreaking Villains Competence Matrix and Evil Magnitude vs. Competence Quadrant. Perfect for citation in arguments, dinner parties, or future congressional hearings.